Mega-sequence 5 (MS-5) – Albian and Cenomanian (duration ~ 19 Ma)

Mega-sequence 5 (MS-5) – Albian and Cenomanian (duration ~ 19 Ma)

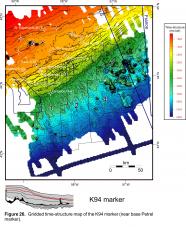

The onset of MS-5 is marked by an abrupt seaward shift is shelf sedimentation above the Naskapi Member of MS-4, with a corresponding abrupt decrease in reflection character on the slope above the Missisauga fan complex. Its lower boundary is the earliest Albian K112 surface described in the previous section. Weston et al. (2012) identified a maximum flooding surface located near the Aptian/Albian boundary (near the top of the Naskapi Member), which we interpret as the base of MS-5 on the shelf. Its upper boundary is the K94 marker that roughly corresponds to the base of the Petrel Member of the Dawson Canyon Formation (see Wade and MacLean, 1990). As such, MS-5 is time-equivalent to the Logan Canyon Formation (minus the Naskapi Member) and the lower half of the Dawson Canyon Formation (Fig. 4).

A notable feature of MS-5 is the sharp contrast in the thickness of outer shelf versus slope sediments (Fig. 24). Much of the outer shelf during MS-5 was located seaward of the SGR, on the present-day upper slope. Significant growth took place in the landward parts of Parcels 1 and 2, across a series of northeast-trending normal faults located seaward of the SGR (Fig. 25, 26). MS-5 increases in time-thickness from about 700 ms (twt) above the SGR, to over 1200 ms (twt) across these faults. The thickest part of this MS-5 shelf-margin system is 18 to 25 km wide and forms a linear northeast-trending thickness anomaly that can be followed along strike for more than 120 km. These outer shelf deposits record a complex stratigraphic history with two clear cycles of aggradation, followed by erosional truncation, and followed in turn by progradation of clinoforms (e.g. profiles D1, D2 and D3 in Figs. 10, 11). Although no wells penetrate the thickest outermost shelf parts of MS-5, several wells have sampled alternating intervals of shale and sandstone in more landward positions. Overall the log motifs are serrated, but numerous stacked 10 to 30 m thick sandstone intervals in Sachem D-76, South Griffin J-13, Louisbourg J-47, and SW Banquereau F-34, have blocky to regressive log motifs that alternate with 5 to 50 m thick shale intervals. Sands are particularly well developed immediately above the Naskapi Member, within the Cree Member of the Logan Canyon Formation (Fig. 4). We tentatively correlate these sands with the lower interval of progradation in MS-5, with the younger period of progradation tentatively tied to the sandy Marmora Member of the Logan Canyon Formation (see Wade and MacLean, 1990).

The youngest and seaward most clinoforms of MS-5 are commonly eroded by a prominent unconformity or are capped by a highly deformed interval where numerous detachment faults in younger strata sole out. The maximum regression of the margin, in post-Triassic times, was achieved during MS-5, and we place a Late Albian to Cenomanian shelf-edge trajectory just landward of Tantallon M-41, in present day water depths that exceed 1000 m (Fig. 25).

Shortland fan complex

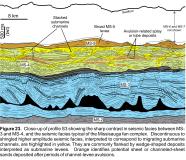

Unlike MS-4 that is characterized by a mix of high and low amplitude reflections on the slope, MS-5 is characterized by distinctly low amplitude to transparent seismic facies with subtle wavy internal reflections (Fig. 23). Tantallon M-41 penetrated the toe-sets of seismically recognized clinoforms located < 5 km seaward from a proposed Albian shelf edge (shelf-edge trajectory 6, Fig. 25). The well encountered principally fine-grained deposits, with a 23.5 m long conventional core containing ample evidence for mass wasting (Piper et al., 2010). Given its location relative to the steep shelf edge, evidence for mass wasting is not surprising. Seaward of the well location, the transition from MS-4 to MS-5 records a significant reduction in the amount of sediment stored on the slope, and a significant change in the architecture of slope deposits. Time-thickness maps indicate that MS-5 consists of a series of 3 to 15 km wide downslope elongated sedimentary ridges that separate numerous 2 to 8 km wide canyons west of the SWLS (Fig. 25). The ridges, which are up to 550 ms thick, can be tracked from the base of the Albian-Cenomanian clinoforms for 90 to 110 km down the slope. They form downslope thinning wedges on dip profiles that pass through their thickest parts (e.g. profile D1; Fig. 10). Coincident with their downslope decrease in relief, canyons between ridges become broader and gradually merge with adjacent canyons to form a largely erosive lower slope. On the basis of their wedge-shaped external form and their low amplitude seismic response, these ridges are interpreted as mud-prone levees that formed from the overspill of fine-grained turbidites.

We refer to this network of empty canyons flanked by muddy levees as the Shortland fan complex. The transition from the Missisauga fan complex below to the Shortland fan complex above is marked by the onset of intense slope bypass, with distinctly non-aggradational canyon floors. With the exception of the finer grained upper parts of turbiditiy currents that overspilled canyon margins and accumulated in levees, little sediment appears to have been stored on the slope during MS-5. These observations mark an important change in the behaviour of sediment gravity flows above MS-4 (discussed in more detail later).

Where preserved, MS-5 strata show clear thinning above the flanks of piercing salt diapirs shown on figure 24 (e.g. central parts of profiles S1 and S2; Fig. 12a), and commonly thin above the crests of lower slope folds that inverted MS-4 strata (above the toe of the BSW). Some canyons also appear to divert around these toe-folds. These observations indicate that these structure were actively growing during MS-5.